Reading this, you probably fit into 1 or more of these 3 categories. 1) You are looking to invest money, 2) you have money sitting on the sidelines and are frozen into inaction or 2) you already have money invested. The 2 questions that drive your decision making are, “What is the future purpose of that money and (more importantly), how long will that money be invested for? In other words, if Point A is today, when is Point B for you?

The answer to that question if the very foundation of how you should respond to investing your money. Write down the answer right now so you can keep revisiting it as we go through this and be able to stick to it. Mine is, God willing, 43 years from now which is when I’ll be 100. Knowing that time frame and visualizing it will help you not take your eye off of Point B. Not being able to do that will most likely mean that you’ll never achieve the money you need to get you to point B. This focused discipline is probably more important today than it has been in over 20 years.

There are a few distractions that keep people from taking their eye off Point B. The first is, discomfort or anxiety. Everyone wants as little of those 2 things as possible. Experiencing none of those is even better. The problem with that path is… there no such path. It doesn’t exist. You just have to look at the exercise and dieting arena. All kinds of food, equipment, drugs and more on the market but, people still are trying to find the easy fix. Will they find it? No, despite what all those ads claim.

Making long-term investment decisions based on how you feel today has never proven to be a successful long-term strategy. If history is a guide, making long-term investment decisions based on how you feel in the middle of a crisis usually results in the average investor never attaining their Point B goal. In chronic cases (making the same mistake over and over again) you’ll slowly move backwards (I’ll show you some stats on that later on).

Those people who sold based on fear a few months ago, or were sitting on more cash than they need to live on, are for the vast majority, still holding cash. People are fearful today (Point A). As such, are willing to accept less than 1% a year in return for feeling comfortable. If you believe inflation will continue to average 2 – 3% annually like it has in the past, then that means anyone holding cash they don’t need for living expenses is guaranteeing themselves an erosion of their savings. What makes them feel comfortable at Point A today means they won’t get to their Point B.

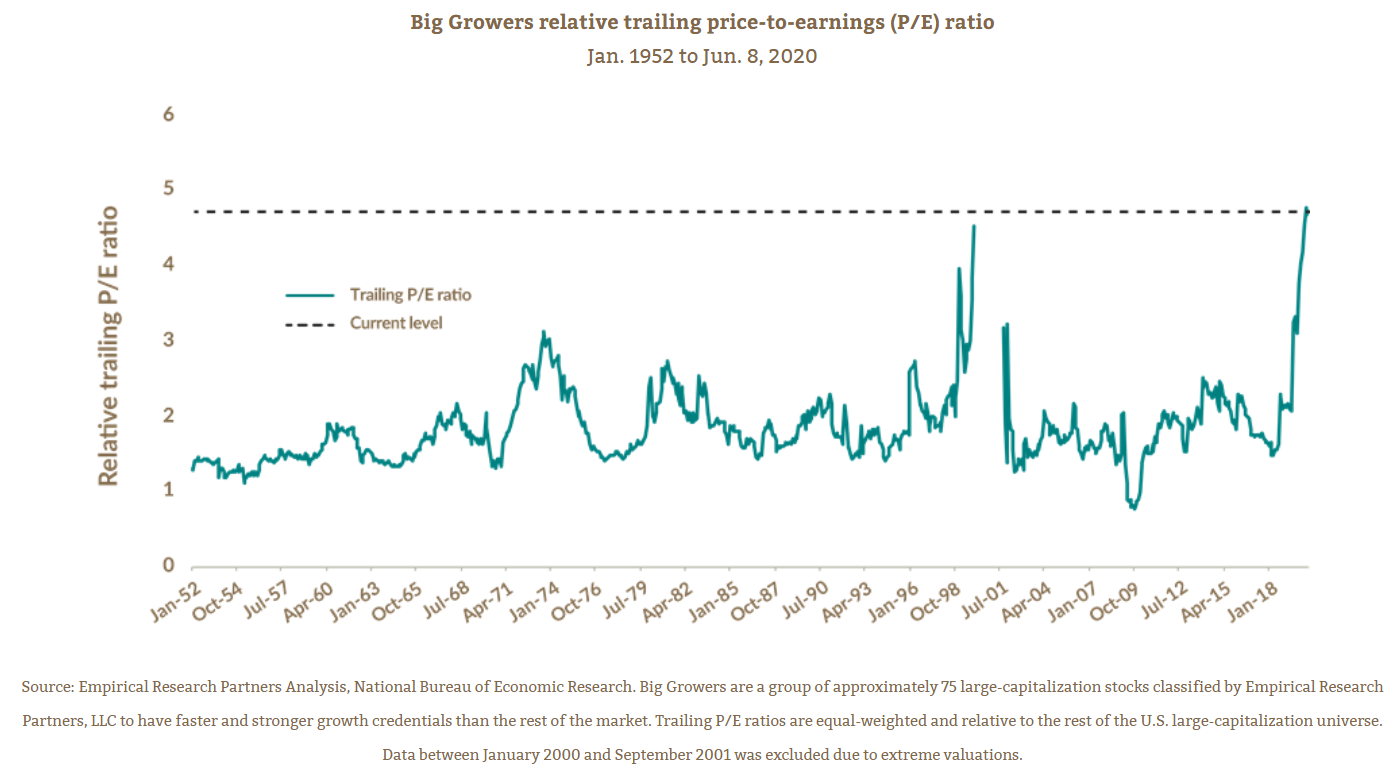

Then there is the other side of the scale, the people investing in companies that we deem as the “obvious survivors”. With every day their share prices go up, more people become new investors, cashing in what they see as a sure way to make money. Very few are looking at the price being paid for these businesses. No one seems to be questioning the rational of paying upwards of 100 times earnings (or more) for a business. 100 times earnings simple means you are getting paid 1% earnings on your investment. All that is being measured is, “my investment is increasing in value thus it must be a good investment”. That is a recipe for a permanent loss of capital and that will happen once reality sets in. I’ve seen this large scale herd mentality before, more than once.

The chart below shows how richly valued the “obvious growers” are today relative to the rest of the market. This chart represents 75 of the fastest growing companies in the US out of 830. It shows that since 1952, people have almost never paid more than today, for the comfort of owning obvious growth businesses. In other words, the few big companies whose shares we have seen go up so steeply, are more expensive today than they were just before the tech bubble burst.

This isn’t to say that these big, growing companies aren’t really good businesses. They are good businesses. The fact is, many of them are great businesses. The issue has to do with price; what you have to pay to own these businesses at today’s prices.

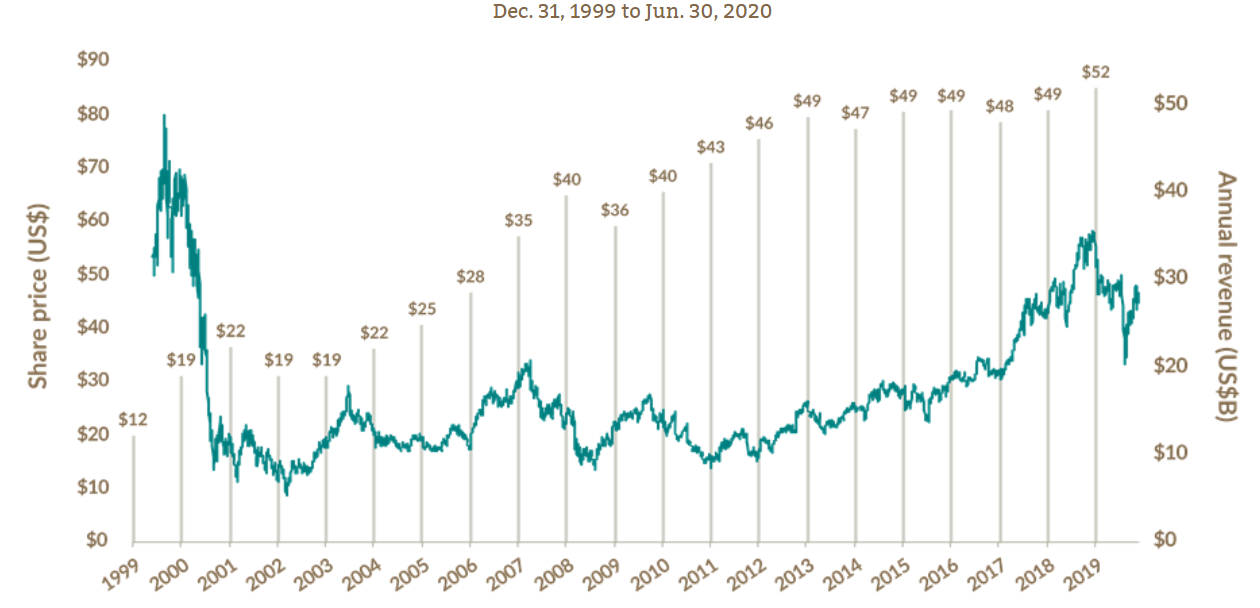

All we need to do is go back a little over 20 years to show the devastating effect that paying too much for a business can have on your wealth. In 1999, everyone knew the internet was about to go through an explosion of growth. One big company sold the “plumbing” required to make data move around the internet. As such, everyone knew this business was going to grow quickly into the foreseeable future. Fast forward 20 years and we can say that everyone who thought that was right. Over the past 20 years this company’s revenues increased by about 330%. However, in spite of this growth, had you made an investment in that 1 big company in 1999, the value of your investment today would be much less than what you invested over 20 years ago. How can that be, you ask? Because you would have had to pay too much to own it. Almost everyone felt comfortable and very good owning shares of this business in 1999. Why wouldn’t you? It was obviously going to do well in the future. However, the price of the shares was way too high based on the annual revenues. The decision making, driven by comfort while ignoring price, has produced a permanent loss of capital. At best, you may have to wait another 10 years to break even.

The inescapable reality of investing is that the price you pay for an investment will dictate your future return. If you pay too high a price for a great business, you can still lose money. That is, despite it being a leader in its field and being highly profitable. Overpaying for an investment doesn’t help you get to Point B, no matter how comfortable it makes you feel today. Also, just because most everyone else owns it, doesn’t make it a good investment either. The masses have proven wrong before and I’d suggest to you, based on what I have seen over my 33 years of doing this, is they will be again.

So, what have our portfolio management teams been buying over the past few months? Here are some example of investments that could prove to provide very healthy returns over the next 3 – 5 years. They have wanted to own some of these businesses for the past 10 years but the prices were too high. However, Covid-19 changed that and thus, the investments were made for themselves, for me and for my client’s portfolios:

- We purchased a business that will benefit from fewer people taking public transit and more people using private vehicles going forward. This same business will benefit from the average age of the cars on the road increasing, which usually happens during a recession. The business has more than doubled its earnings per share in the last five years and we think it can do the same over the next five years. When we started buying it, we were being asked to pay approximately 14 times earnings for it. We aren’t paying for the future growth that is expected. In other words, we’re getting future growth for free.

- We purchased a technology services company in Japan that should be able to double its profit margins in the next three years while also growing its revenue. Japanese companies have underinvested in IT infrastructure for decades and it’s finally caught up with them. Their spending in this space will increase and this company has one of the best solutions to help. When we bought it, it was trading for around 10 times earnings. Again, we’re getting future growth for free.

- We purchased a global quick-serve restaurant business that saw the majority of its businesses stay open during the Covid lock downs. This company owns three brands and today two of them are experiencing flat-to-moderate growth on a year-over-year basis. Looking forward, we believe all three brands have room to increase their profitability, but one brand in particular has the potential to more than quadruple in size. This business has more than doubled its earnings in the last five years. When we bought it, it was trading for around 10 times earnings. And, as with the others just mentioned, we aren’t paying for the expected future growth.

- We purchased a global propane distributor. Homes still need to be heated and cooled, pandemic or not. This business came into the crisis with absolutely no debt, which puts it in a good position to acquire market share going forward. The management team has a long history of completing acquisitions that have benefited shareholders, and now the company has the perfect environment and balance sheet to complete even more acquisitions. They are a great operator, as evidenced by their ability to increase profits for the last eight consecutive years. We think they have a chance of increasing their earnings by almost 70% in the next five years. When we bought it, it was trading for around 14 times earnings (and again, we’re getting future growth for free).

- We purchased one of Canada’s largest apartment building owners. This business has grown its revenue organically and reduced its expenses. The management owns over 25% of the company; they are owners along with us. During the crisis, the share price declined by more than 60%, providing us with the opportunity to buy assets for well below what they are worth. We took advantage of the opportunity to buy apartment units in the public market for roughly half of what they would sell for if bought privately.

- We increased our ownership in a global investment firm that mainly invests in private businesses. As stated on its website, the firm delivered annual investment returns of 27% before fees for the last 36 years. It invests its own money alongside their investors. When we bought it in the middle of the crisis, what we paid for it was approximately the value of the firm’s cash and securities on its balance sheet. Our best estimate is that before accounting for any future growth, we purchased the company for half of what it was worth. We weren’t even being asked to pay for its existing assets, let alone it’s expected future growth.

Now, with all of that said, holding these investments now may not appear to be delivering results as you see on a portfolio statement. I know, this can be hard to take when you see other investments increasing in value much quicker. I’ve seen highly disciplined investment managers, with excellent long-term track records look wrong in the short term. Sometimes this “short term” has been for a few years. What matters the most is long-term outperformance and to get that, you need to be disciplined. Here are some examples of the mistakes the vast majority make. These are from a booked called “The Big Secret for The Small Investor” by Joel Greenblatt, a highly successful investor in his own right, estimated to be worth $500 million.

In this book he recounts how overall stock market performance was essentially flat during the decade from 2000 to 2010, yet the best-performing mutual fund returned 18% per year. I’m sure anyone would be happy with that. How did the funds’ investors do? On average they lost 11% a year on a money-weighted basis. How do you lose 11% per year in an investment that compounds at 18% annually for 10 years? It’s easy really. Invest when it’s doing well and sell it when it’s doing poorly. This is what investors do when they’re not willing to look wrong in the short term. This is only 1 example however I’ve seen it reported by many retail investment pools.

Greenblatt also analyzed the top quartile of investment managers over the 2000 to 2010 period (i.e., those who outperformed 75% of their peers), and showed that:

- 97% of managers with the best 10-year record spent at least three years in the bottom half of the group.

- 79% of managers with the best 10-year record spent at least three years in the bottom quartile (bottom 25%) of the group

- 47% of managers with the best 10-year record spent at least three years in the bottom decile (the bottom 10%) of the group

For much of the time, the most successful investment managers appeared hugely wrong for 1/3rd of the time. So, you too have to be willing to look wrong in the short term to be right in the long term. Point B is your long term. Stay focused on that and you’ll get there.